I have been thinking a lot about stigma and its implications for people with substance use disorders and/or chronic pain. Stigma is defined as “an attribute or quality which significantly discredits one in the eyes of others.”[i]

The Fear of Stigmatization

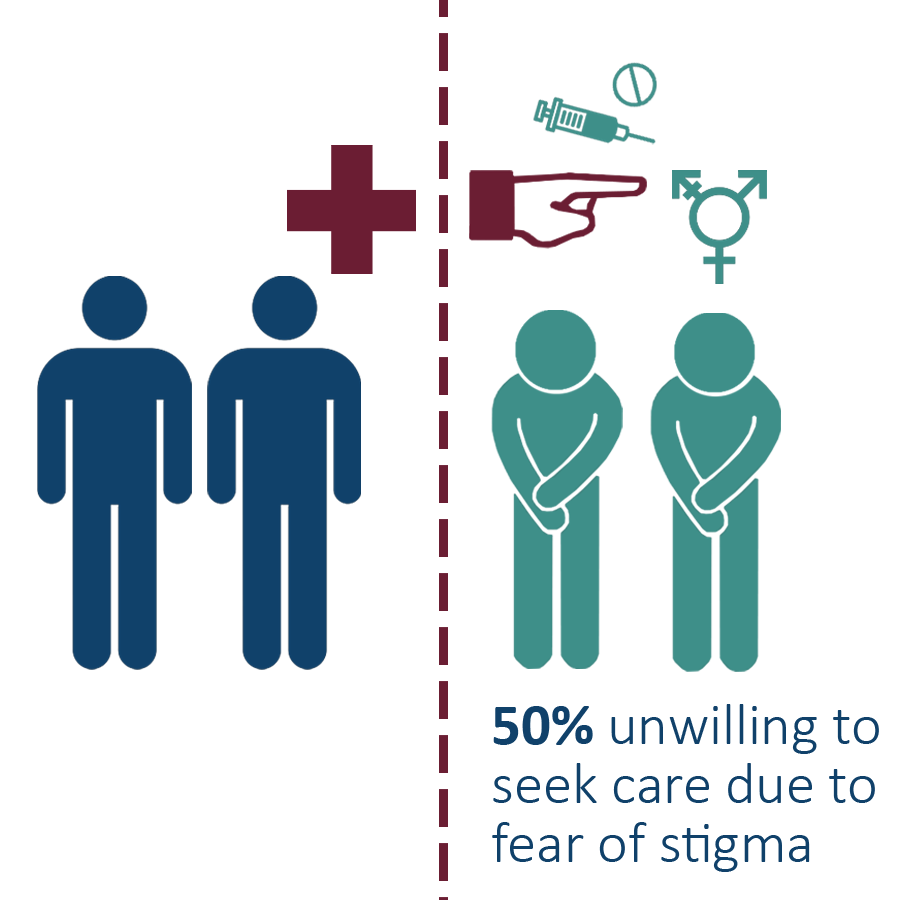

At a recent session of the Community of Practice for Housing and Harm Reduction, the Edmonton Men’s Health Collective (Peer N Peer) presented some alarming statistics. In a survey of participants in the peer support program, 50% of the patients were unwilling to go to a family doctor or primary care clinic due to fear of being stigmatized for both their substance use and their sexual practices.

Wow – imagine if 50% of our diabetic patients were fearful of stigmatization to the degree that they would not come to our offices. Stigma stops people from accessing care they need within the system, and this can lead to worsening health outcomes and even death.

Olsen identified four factors involved in the stigma surrounding substance use disorders. First, a belief that addiction is a wilful choice and not a chronic relapsing and remitting disease. Second, the separation of addiction treatment from the rest of the health care system. Third, the language used surrounding addiction, and finally the criminal justice system not accepting medical judgement in approaches to addiction.[ii]

Language Matters

So what do we do about it? Language matters. In our province, we have political leaders who use the term “illegal drug sites” for supervised consumption services. That in itself is leading to stigmatization of people who use substances in the press. As health clinicians, we need to challenge that, and we need to look at what we say.

Let’s stop using terms like addicts, drug seekers, drug abusers, and instead use “person first language” like people with substance use disorder or people who use substances. Let’s stop saying urine is clean or dirty – use urine is negative or positive for substances. Let’s stop using the patient is “non-compliant” and instead use patient is not in agreement with the proposed treatment plan. We need to ensure our words do not stigmatize people even more. There are several great resources to use in your clinics or offices.[iii][iv]

Sadly, the issue runs much more deeply than in words. It is embedded in our health care system.

Breaking Down Implicit Bias

I recently read an article in the New England Journal of Medicine regarding endocarditis care.[v] Dr. Michael Incze reflected on a follow-up of his patient who recently had been discharged after a diagnosis of endocarditis related to underlying opioid use disorder. Although she had received the appropriate antibiotics and diagnostics, the underlying cause of her endocarditis was not fully addressed nor followed. She was started on buprenorphine naloxone, but the waiver to allow for further prescriptions was not processed. What’s more, portable oxygen was not provided, her cardiac surgery follow-up was not relayed, and there was a policy for her to be on OAT for a length of time to receive the valve replacement she badly needed. She needed that wrap around care provided in primary care, but also follow up on the critical underlying diseases like her opioid use disorder, and a replacement of her heart valve. Without advocacy by her primary care team, she would have slipped through the cracks of a system that treated endocarditis from a substance use disorder differently than when it occurs from other causes.

In this case, there was separation of medical care and addiction care in addition to a multitude of barriers to access. She had needs at home that were not addressed upon her hospital discharge. The urgency of need for adequate opioid use disorder treatment was not recognized. She was required to be abstinent and stable on OAT before being considered for valve replacement. I have seen a similar case in my own practice, where surgery was delayed despite significant cardiac failure due to a destroyed valve, until she was considered stabilized with respect to her substance use. I have to wonder, if these women’s chronic disease was diabetes, would the surgery be delayed for six to eight weeks until their diabetes was stabilized for that length of time?

“The language and the health system policies all serve to reinforce the stigma on substance use that people then internalize – a deep-seated shame and feeling in patients that they do not deserve the same treatment that other people get for their chronic conditions.”

Similarly, I looked at the requirement, for alcohol abstinence for six months before liver transplantation for alcohol related cirrhosis.[vi] There is no good evidence that people abstinent for six months prior to transplant are less likely to relapse in their alcohol use disorder than those who have not. A personal case that haunts me to this day, involved trying to advocate for a patient to receive a liver transplant when they had alcohol use disorder and end-stage cirrhosis. This young person was refused transplantation as they had not been abstinent and died; leaving behind two young children. I cannot help but wonder if this patient had autoimmune hepatitis with cirrhosis, if the outcome would have been different.

The language and the health system policies all serve to reinforce the stigma on substance use that people then internalize – a deep-seated shame and feeling in patients that they do not deserve the same treatment that other people get for their chronic conditions. My young cirrhosis patient explained to me that she accepted her death as she “deserved it”. This is the end result of stigma.

So, what am I trying to say? I think that we all have implicit bias and need to really examine where stigma around substance use disorders is reflected in our offices, our practices, our emergency rooms, and in our hospitals. We can start by simply changing the language around addiction. We can educate our staff and our patients. We can challenge the resource allocation, and policies that reduce access to care based on medical conditions, such a substance use disorders. Most of all, we can support our patients in the health care system by providing addiction services with the system together with our patient at the centre of care.

Cathy Scrimshaw, BSc (Hon), MD, FCFP

Medical Lead

Collaborative Mentorship Network

Endnotes:

[i] https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-09/CCSA-Language-and-Stigma-in-Substance-Use-Addiction-Guide-2019-en.pdf

[ii] Olsen Y, Sharfstein JM. Confronting the Stigma of Opioid Use Disorder—and Its Treatment. JAMA. 2014;311(14):1393–1394. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.2147

[iii] https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/nidamed_words_matter.pdf

[iv] https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-09/CCSA-Language-and-Stigma-in-Substance-Use-Addiction-Guide-2019-en.pdf

[v]N Engl J Med 2021; 384:297-299

[vi] Im GY, Cameron AM, Lucey MR. Liver transplantation for alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2019 Feb;70(2):328-334. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.11.007. PMID: 30658734.

2 Responses

Thank you for this. As physicians we need to show compassion and to model better ways to think and talk about addiction. You make good points regarding patterns of stigmatization, language use, and implicit bias. These patterns run deep and they change over time (more on this below). Collectively we physicians have significant influence on society’s norms.

We can start with ourselves. We all have biases. Not judging takes real effort. We owe it to our patients to practice conscious acts of benevolence. No one should be undermined so thoroughly that they feel they deserve to die.

Regarding language, I agree that we need to monitor and revise our own and to call out politicians who weaponize it. Like you I find the term “noncompliant” cold and dehumanizing. I assume it’s from an age when doctors decided and patients, like children, did as they were told. Best to junk it. Overall, though, I’m not so sanguine about the power of words. Neither am I comfortable with the exaltation of the medical model by emphasizing addiction-as-disease.

IMO we should acknowledge that patients suffering from addiction still have agency. Anyone who doubts it should ask an oncologist how many nicotine addicts who are told they have lung cancer suddenly, if belatedly, make a “wilful choice” to quit smoking.

A friend is a renowned foodie; nobody declines an invitation to dinner. His passion has left him obese and diabetic, with a history of colon cancer. Yet he repeatedly, knowingly, and joyfully continues to indulge in behaviour that harms his body. Is that not a definition of addiction? How much of his behaviour (addiction) should we attribute to choice? It’s obviously not zero percent, it’s equally obvious that his problem is not reducible to “Just say no”.

When obesity was rare it was stigmatized almost as much as drug addiction. Today 43 percent of adult Americans are obese. Ted Cruz’s 300-lb campaign manager feels free to mock the opposing campaign manager’s low weight and characterized him as scrawny, insecure, and weak. To the best of my knowledge no one called him out for slim-shaming.

Social stigma change. There was a time when no one stigmatized smoking. In 1954 a GP advised my mother, then pregnant with her fifth child, to take up smoking in order to limit weight gain. Happily for me, she didn’t.

Today we shun smokers and fear being accused of fat-shaming. We still, however, feel it’s okay to stigmatize people who seek pleasure from drugs.

The history of obesity sheds light on the role of language. Did labelling obesity help us to help patients? The NIH declared that obesity is a disease, not a behavioural problem, in 1998. Since then obesity rates in the US have risen from 30 percent to 43 percent.

So much for the power of rebranding. Stephen Pinkner of MIT has written extensively on stigmatization and the limits of language (google “Pinkner, euphemism treadmill”). Obesity is less stigmatized today because the number of obese people reached the point where they could push back, not because doctors declared obesity a disease. By comparison the drug-addicted population is relatively small. It will never have the lobbying power of the obese.

Refocussing on the medical model might have some benefit. Downplaying behavioural factors should assuage guilt. Physicians’ conversations with addicted patients might be less confrontational. On the other hand, I see no reason to think that medicalizing and relabelling the problem will help us to limit addiction. It certainly didn’t help with obesity.

I suggest we need a balance. Yes, addictions are chronic relapsing/remitting diseases but, with apologies to Olsen, there is also an element of choice. We are not disease-driven automatons. Denying patients’ agency infantilizes them.

I agree that health care institutions must reduce implicit and explicit structural bias. It won’t be easy. Reforming the judicial system might be harder. In the meantime, each of us can question our own approach — our language, our potential biases — and clean things up.

I read with interest the thoughtful reply to my blog post on Stigma, by Dr Clark. I appreciate this perspective.

I do have a bias to declare in that my background is in cellular and molecular biology and the medical model of addiction with the evidence of molecular level changes influences my opinion. The advances in understanding the role of neurobiology in addiction along with evidence from epigenetics supports the idea of a complex disease process influenced by psychological and social contexts in my opinion. How does personal agency fit into that model? An excellent question.

Thanks you for your thought provoking post.

Cathy Scrimshaw