By Dr. Leah Phillips

“Illness is the doctor to whom we pay most heed; to kindness, to knowledge, we make promise only; pain we obey.” – Marcel Proust

All people feel pain; pain is unavoidable. Yet for some, pain is an uninvited dictator in their lives. It taunts and angers them from the beginning to the end of each day… every day. As Proust notes, “pain we obey” because for some, pain never stops, it never rests; and it controls every aspect of their lives.

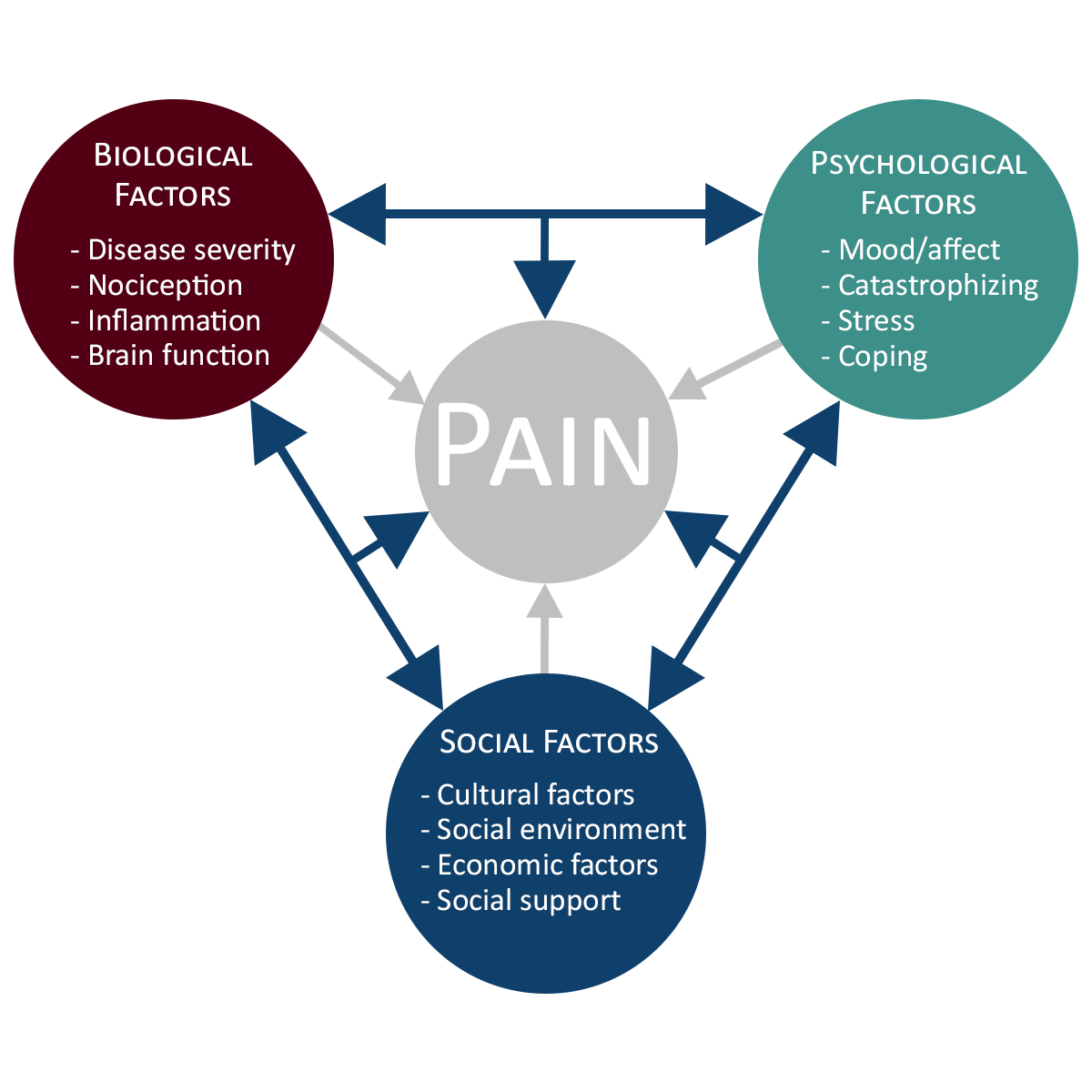

Chronic pain is generally understood to be a biopsychosocial issue. First proposed by George Engel in 1977i, the biopsychosocial model of pain proposes a reciprocal interaction between a person’s emotional state, their environment (e.g. work or home life), and physical tissue damage. This unique interaction can have a profound effect on how individuals respond to treatment and live with chronic pain.

Identifying the unique and interactive roles of all these factors is difficult to unravel; we often refer to long term pain as complex. This complexity is precisely what the biopsychosocial model is getting at. Therefore, research that only examines single factors, without including interactions, leads to some potentially interesting clues but fails to fully capture the complex nature of pain and the complex treatment that is required.

Change the Research

Research on chronic pain needs to change. Simple regression models have failed to reveal that one golden causal factor, and I dare say, this is because it does not exist. Understanding a complex health issue demands complex research. I would like to see medical (epidemiological) research expanded; to go outside its comfort zone… where? To the humanities, the social sciences, and to alternative complementary medicine. Not just because there is good evidence available but because understanding how someone’s psychology and sociology interact could suggest a greater and deeper understanding of their unique situation and could reveal lasting adaptive strategies to manage their chronic pain.

In my own research, I sought to better understand how pain coping, (how individuals manage or minimize the negative impacts of pain) affects the recovery process (recover does not always mean cure). Research in this area indicates that individuals’ personal appraisals of their situations can directly influence their potential for recovery. As noted above, the phenomena of chronic pain is complex, it’s difficult to treat and cure. Therefore, identifying modifiable positive pain coping strategies can help people manage and live with pain.

“Rather than trying to ‘cure’ chronic pain, we might want to think about ways we can help people better manage their pain. We do this by being curious, getting to know how individuals think and feel about their pain, getting to know their ‘pain story’, and finding out what they expect for recovery.“

But not all ways of coping with pain are the same… some are more person-based (perceptual) while others or more cogitative (situational).

Interestingly, person-based coping mechanisms tend to be more detrimental to recovery. Perhaps because changing a deeply rooted belief requires intense personal work. The most commonly studied perceptual pain coping mechanism is catastrophizing, thinking that the pain is never going away and nothing is ever going to help, is commonly understood as a maladaptive coping strategy. Other maladaptive perceptual coping mechanisms include: fear avoidance, negative self-talk, and helplessness.

On the other hand, there are some coping mechanisms that have been shown to have a positive impact on how people manage their pain. These include belonging or subscribing to a spiritual practice or diverting attention from the pain using practices like mindfulness and reinterpretation of pain sensations. In addition to these situationally based adaptive coping mechanisms, there is evidence to show that perceived control has some influence over a person’s ability to live with pain. Jensen et al.’s critical review of the pain coping literature found that patients who believe they can control their pain, who avoid catastrophizing about their condition, and who believe they are not severely disabled, appear to function better than those who do not.

So, what’s the bottom line?

Rather than trying to cure chronic pain, we might want to think about ways we can help people better manage their pain. We do this by being curious, getting to know how individuals think and feel about their pain, getting to know their pain story, and finding out what they expect for recovery. Once this is understood, it can be rewarding to work alongside them to co-design a treatment plan that includes activities that align with their values and lifestyle. Not only does this help reset expectations, this collaborative therapeutic interaction can minimize fear, redirect negative self-talk, and lead to a better quality of life.